A $100 utility bill in 2010 would be $207 in 2020, as Peel Region shifts costs from the property tax base

In a sprawling Port Credit property, an accountant turns on the shower to prepare for the day. At the same time in Malton, a single parent is helping his children wash up before school.

It’s the same morning ritual both have gone through five days a week for years.

The Port Credit waterfront in Mississauga

In Port Credit, the accountant has seen little change as of late when it comes to finances. Each year, the city and region pass tax increases for his sizable property, which is negligible compared with the percentage of his salary that’s passed to the federal and provincial government. The accountant’s comfortable paycheque has increased in tandem with inflation, as has his property tax bill.

However, for both the accountant and parent, a much less scrutinized cost has been rising.

Much of this cost is for a human right recognized by the United Nations — the price of water.

For years, while mitigating unpopular increases to its property taxes, the Region of Peel has been pushing up its utility bill, sometimes by as much as 9 percent.

Over the past decade, the increases to the Region of Peel utility rate have been so severe that a $100 bill in 2010, based on the previous year’s rate, would cost $207 in 2020 for the same amount of usage.

This represents a compounded increase over the last decade that is five times the rate of inflation in Ontario over the same period.

And things might only get worse.

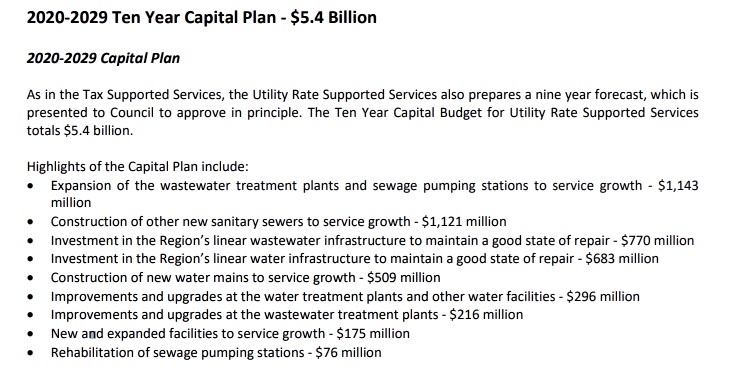

The 2020 budget document from the region reveals a startling reality. There is currently a $1.4 billion gap in the utility rate-supported budget, with capital infrastructure to provide utility services across Peel in dire need of more money.

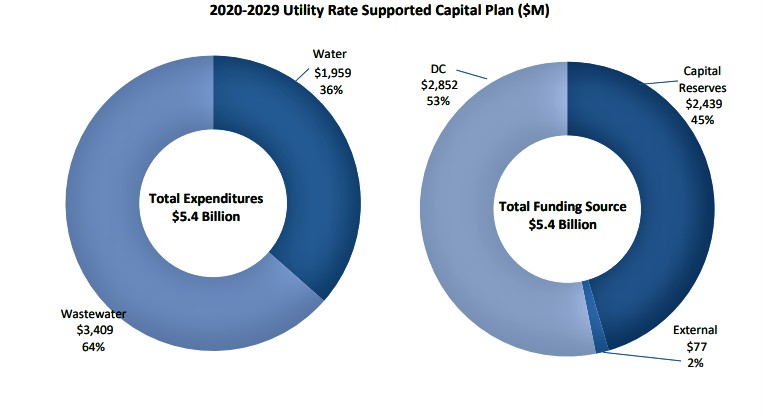

The need: $5.4 billion over the next decade, if Peel Region residents want their water to keep flowing in and out properly.

This means extremely sharp increases to property owners for at least the next ten years. On top of 2020’s 7.2 percent increase in the utility rate, next year’s hike is already projected to go up by 7.3 percent, and that number could rise, just like it did this year from the original 2020 projection of 6.3 percent.

Small business owners are being hit even harder.

Their utility rate increase in 2020 alone will cost $136 extra, on average. That’s almost double the extra cost homeowners, on average, will face this year for the property tax increase.

For property owners, particularly seniors on a fixed income struggling to make ends meet, the utility increases have been an unrelenting rise, disproportionately impacting residents who have less household income.

The region’s dramatically increasing utility rate was a topic of discussion during the first deliberations over the Region of Peel’s most recent budget. “We need to get a better handle on smoothing those utilities rate increases going forward [...] we just have not been really consistent,” Mississauga Ward 9 Councillor Pat Saito said in November. Referring to the past 15 years of regional budgets, she added that “there were years where we reduced the rate, there were years where it was zero and then a year later we skyrocket it to 7 or 8 percent.”

Mississauga Ward 2 Councillor Karen Ras and Ward 3 Councillor Chris Fonseca echoed Saito’s sentiment, asking for a fixed or variable utility increase to be put in place for future years. In response to the request, Region of Peel Commissioner of Public Works Andrew Farr, said a team was working to review the utility rate and was looking to adopt a more structured, long-term philosophy in time for the 2022 budget.

But, just a few weeks later, the conversation was forgotten. In order to meet Mississauga Ward 7 Dipika Damerla and Brampton Mayor Patrick Brown’s request to increase the regional budget by no more than 1.5 percent, staff pushed up the region’s utility rate. Achieving a reduced tax increase partially by removing a planned $2.4 million property tax-supported subsidy of the utility budget, which will now see a 7.2 percent increase in 2020 instead of the initially proposed 6.3 percent utility rate hike.

So instead of using utility rate stabilization policies from the property tax-supported budget, a growing gap has emerged in funding for the region’s utility infrastructure.

Despite this backward step, the councillors’ now-forgotten comments were on the money. Including 2010, the utility rate in Peel has risen annually over the last decade by staggering percentages: 5, 9.1, 6, 7, 7, 7, 9, 5, 6.5, 6.5, 7.2.

This is unsustainable.

While the price of a bottle of water has been steady for years, the cost of drinking from the tap in Peel has skyrocketed.

In some cities, a well-documented use of the utility rate has taken place. Perhaps the most blatant example of the blurring of lines between a property tax-supported budget and the utility rate-supported budget exists in Winnipeg, where rates have been set for the long-term. According to the Winnipeg Free Press, the city will “siphon” more than $700 million from its utility rate across the next decade into “dividends” that go straight into its general revenues. The scathing article describes the practice as “nothing more than a backdoor tax grab,” with a percentage of the utility rate spent on projects across the city that relate to neither water nor wastewater.

In Peel, the practice is to openly put all water and wastewater costs on the utility bill, including infrastructure such as new water and wastewater lines, reservoirs, pumping stations and treatment facilities.

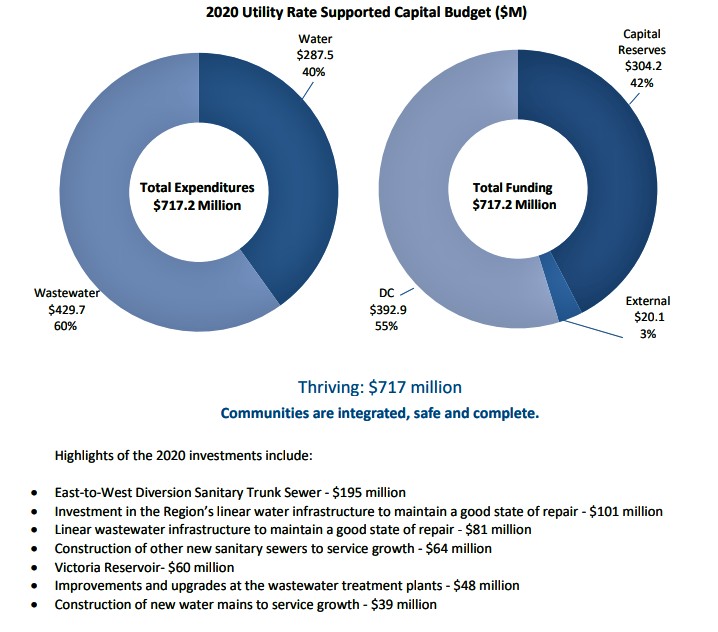

The utility rate supported capital budget alone for 2020 is $717 million, which represents 68 percent of Peel Region’s entire capital budget for 2020.

In every way imaginable, the utility bill is the least considered and publicized budget element despite its significant impact on residents. Whether you rent or own your house, you must pay for the water and wastewater you use, meaning there is no avoiding the fee.

Norman Lum, the director of business and financial planning at the Region of Peel, said the utility rate was not being used to hide tax increases via a spokesperson. He told The Pointer “the water and wastewater services appropriately reflects all costs that support its delivery which includes key internal supports.” It’s unclear from his response if things outside “water and wastewater services” are also included in the utility bill.

He went on to add that infrastructure such as “pipes and the facilities to process water/wastewater” require maintenance. According to the region, the utility rate even covers costs for “local Conservation Authorities,” which, in Peel, includes the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority.

The list of items covered by ever-increasing utility fees features two water treatment facilities, three wastewater facilities, pipes and related reserve funds.

“The water and wastewater services utilize $24 billion worth of infrastructure [...] to provide services to residents and businesses in Peel,” Lum said. “To ensure there is no disruption in service, these assets need to be maintained in a state of good repair by replacing them when they reach the end of their useful life. To have sufficient funds to do this work Peel has required infrastructure increases that have ranged from 3.5 percent to 6 percent over the past decade.”

In a follow-up statement, the region clarified that “a little more than half of the annual revenue” from utilities is used for the capital plan, with the other half used to fund day-to-day operations. The region stated it has “two distinct budgets,” with one funded by the property tax and the other by utility fees.

Explaining the rationale of shifting revenue from the tax-supported budget to the utility rate, Region of Peel CFO Stephen VanOfwegen told council in December that “unlike property taxes, the utility rate is a user fee, a customer can adjust their water consumption to manage their water bill.”

Increasing the usage-based utility rate — which is applied universally regardless of income, rental status or property value — disproportionately affects the poorest in the region.

Region of Peel CFO Stephen VanOfwegen

While it may be easier to refer to water users as customers, the property tax is also designed in a manner so residents (customers) pay for the services they use. The 1.5 percent tax increase approved for the 2020 regional budget is not arbitrary, instead it is a mechanism designed to charge residents for the roads they use, the paramedics they call and the police service protecting them, as well as the garbage collection. But the biggest difference is that the utility rate is based directly on usage, whereas the homeowner who never uses a road or calls the police still pays the same property tax rate as the homeowner who is constantly on the roads and on the phone with police.

Emily Satterthwaite, an associate professor in the University of Toronto’s law faculty, who specializes in taxation, told The Pointer hikes in utility rates are “highly regressive.”

“It’s actually worse than the adoption of an equivalent tax because there may not be the same public debate or awareness that there usually is [...] regarding tax changes,” she added.

With the utility fee rising significantly above inflation each year, it is tough for residents already reeling under the pressure of taxes to cope.

The 2019 Who’s Hungry Report surveyed users of food banks in Mississauga and Toronto, finding the average food bank user has just $7.83 cents left to spend per day after paying for housing. In such situations, laid bare by the research, doubling the price of water for many fixed income earners over the span of a decade, pushes them further to the edge.

The dangers of playing politics with the utility bill was pointed out to councillors in 2017. At the time, Daniel Wong, a public works finance support unit supervisor with Peel Region, explained how usage fees were critical to generating revenue. In 2017, residents had embraced water saving strategies and new technologies, significantly reducing consumption. This good news was tarnished by a fear within the region that falling usage could drastically reduce revenues and lead to either a property tax impact or a rise in the utility rates.

In the following three years, the utility rate rose twice by 6.5 percent and, most recently, 7.2 percent.

A 2016 study by The Fraser Institute found, since 2005, utility rates have risen “faster than residential property tax[es]” across the province. Of the 33 communities included in the research, just four had rates increasing below the GDP rate. In the report, the trend was attributed to municipalities being forced into finally upgrading age-old and “long neglected” water infrastructure, alongside a need to plan for changing environmental factors.

Some cities have moved away from the changeable user fees in favour of a significant number of fixed rates, offering stability in forward planning. In London, Ont., water usage itself only composes around 20 percent of a utility bill, with the rest of the cost being made up by predetermined fixed charges.

In Peel, residents will have to wait until the 2022 budget is released to see more uniform and predictable rules applied to their utility bills.

Until then, all residents, including the poorest in Peel, will remain uncertain about how much of their household budget will go to utilities. Families living below the poverty line, new arrivals in precarious housing situations and food bank users scraping their income together for rent will continue to see the cost of flushing the toilet, showering and washing a dish rise significantly faster than their wages each year.

The next time a councillor says they are keeping property taxes low, they might be reminded that a glass of cold water from a tap in Peel costs twice as much as it did a decade ago.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @isaaccallan

Tel: 647-561-4879

Submit a correction about this story