Crisis Response Teams could be a lifesaver for Peel’s ailing mental health system

Over the last ten years, gaps in care for mental health have rarely been talked about at Queen's Park, despite reaching crisis levels across Ontario.

Last week, Sara Singh, NDP MPP for Brampton Centre, stood up in the Legislature to deliver a heartfelt plea to her colleagues to help those struggling with mental health challenges. At times, Singh appeared to bite back tears as she talked about her own family and friends who have been affected.

“Every single day I hear these stories, these are young people who come up to me at events, they’re parents, my cousins, my brother’s best friend, these are not numbers on a waitlist, these are real families. These are students, some of them as young as nine years old, desperately seeking supports. They deserve better and Ontario’s children can not wait any longer,” she said.

Singh pointed a finger at both the former Liberal government, which she says neglected the mental health system for years, and the current PC government, which has made significant cuts to the provincial budget.

Sara Singh, NDP MPP for Brampton Centre

“Young people are waiting in crisis in Peel and Brampton, on average, some are waiting 737 days for mental health supports. Can you imagine being a young child in a state of emergency and being told you need to wait in a hallway for hours and hours on end in order to get the help you need? Imagine being a parent, grieving the loss of your child because the systems that were supposed to be there to protect your child, failed to protect them every step of the way.”

According to the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA), 1 in 5 Canadians will experience a mental health problem or illness in any given year. At Peel’s current population, that means there could be 276,000 people affected every year. The Peel Dufferin branch of the CMHA estimates that due to current funding restrictions, it reaches less than 10 percent of these individuals. Further, the Peel Children's Centre, the leading agency in the region that delivers mental health programs and services to children and youth, states that with current funding it can only serve 5,000 patients. This means at any time some 41,000 kids, potentially, and 18,000 young adults, are not receiving adequate care.

Without proper supports in place, these illnesses only worsen, and oftentimes lead to crisis, which lands that person in an interaction with police.

For Peel Regional Police, the number of apprehensions they’ve made under the Mental Health Act has been consistently increasing, and the outcomes have not been good.

Now, a new Mobile Crisis Rapid Response Team (MCRRT), announced during a press conference on Friday, will look to keep those suffering out of custody and hospital emergency departments. Officially, funding for the new MCRRT team was announced in May 2019, when the province provided $2.3 million to CMHA Peel Dufferin to assist with service expansion. The teams, which pair a crisis worker with a police officer, are now active in the region, 365 days a year.

“We have a really strong opportunity to build some resiliency in this community,” said Peel Regional Police Chief Nishan Duraiappah during the announcement. “Our model of crisis response, the continuum, not just in crisis, but after crisis and aftercare, can be the model for the entire country.”

Peel Regional Police Chief Nishan Duraiappah speaks at the MCRRT launch event

Chief Duraiappah explained that over the last five years, the number of individuals Peel police have taken into custody under the Mental Health Act has risen by 34 percent, from around 4,000 in 2014, to over 6,000 in 2019.

The consequences of such apprehensions are numerous. In terms of resources, it takes Peel officers off the streets — at current apprehension levels, a pair of officers take a person in crisis to hospital 16 times a day — a particularly concerning effect as the region grapples with a rise in violent crime. Peel police estimate that $1.8 million in salaries was spent while officers were in emergency department waiting rooms with individuals in crisis. It’s not only a waste of money and police time, but these apprehensions are ineffective. Approximately 40 percent of individuals dealing with mental health problems have been apprehended by police at least once — sometimes more — with many of those instances not related to criminal conduct.

Additionally, particularly in the case of Brampton, it puts further strain on a local emergency department that is bursting at the seams. Brampton councillors have declared a healthcare emergency to try and draw attention to the city’s dire need for another hospital and to assist those who are currently ailing in hospital hallways. Having numerous people arrive at the ER who don’t really need to be there puts further strain on the system.

Putting the resources aside, Chief Duraiappah made it quite clear the goal of MCRRT is not to save police time, but to get those experiencing a mental health crisis the help they need.

“No longer can policing see things and do things traditionally the way that it was,” the Chief said. “We’re getting the right care to the right people.”

And the MCCRT teams are working.

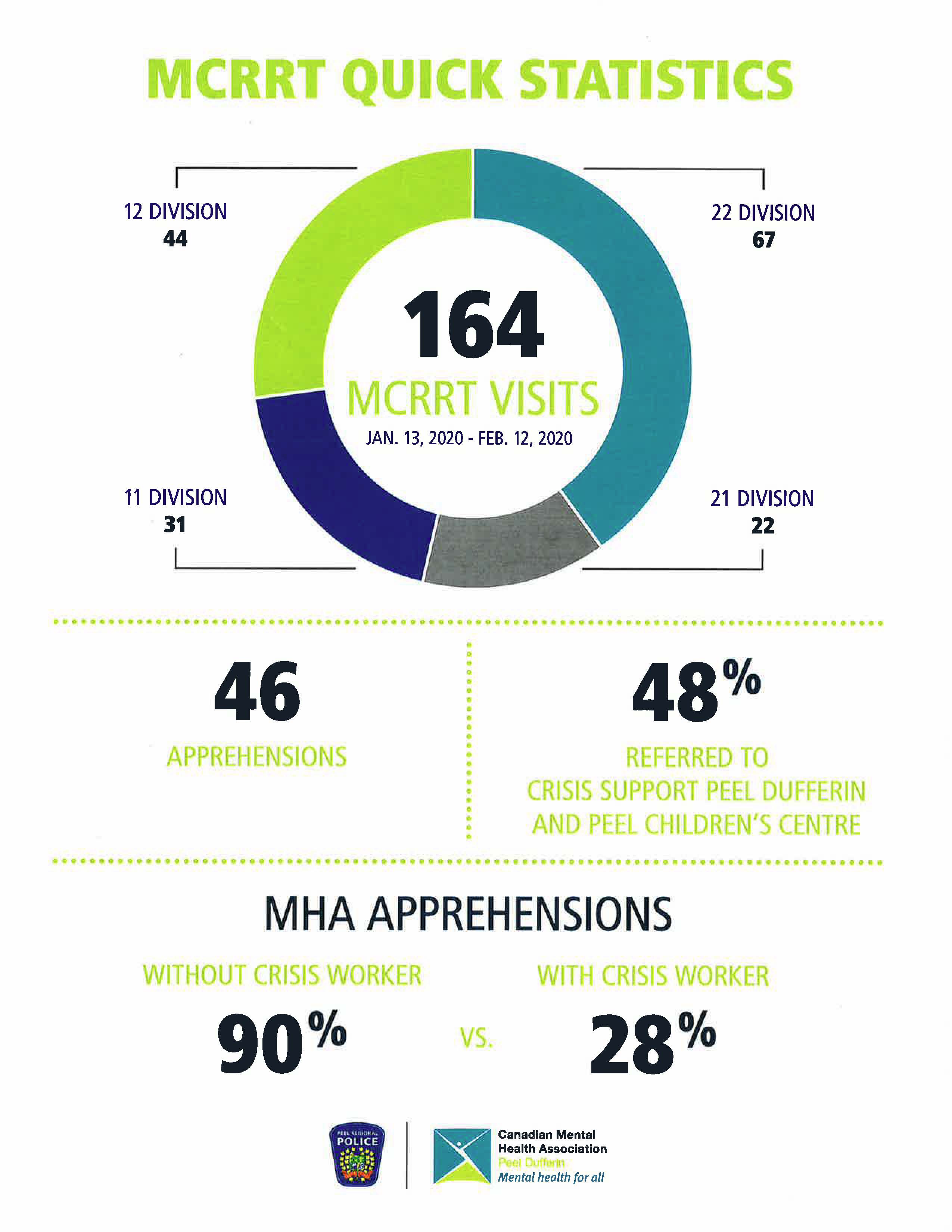

From the program start on Jan. 13, 2020 until Feb. 12, the MCCRT teams were called to 164 instances, of which only 46 led to an apprehension, which is 28 percent of the time. Peel police say that without the MCCRT team, 90 percent of those cases would have led to the individual being taken into custody.

The teams referred almost half of those individuals to crisis supports at the CMHA and Peel Children’s Centre, resources crucial in helping people navigate the complex web of healthcare providers to get them the help they need faster.

“You see we’re actually making a difference in people’s lives,” said David Smith, the CEO of the CMHA Peel Dufferin. “The emphasis on the good of the client as opposed to saving police hours or some of the other benefits that come along has been incredible.”

Similar iterations of the MCRRT model are becoming increasingly common across Ontario as word has spread about Peel’s success. According to a 2019 presentation made to the province’s Human Services and Justice Coordinating Committee, these have grown from less than five programs in the mid-90s, to more than 40 today split between rural and urban municipalities.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @JoeljWittnebel

Submit a correction about this story