Is anyone policing Peel police? Concerns mount about officer misconduct

Marie Henein is one of the most intimidating criminal defence lawyers in Canada, famous for getting former CBC Radio host Jian Ghomeshi off on a bevy of sexual assault charges. A remorseless warrior in the courtroom, Henein's cross-examination skills were on full display in Kitchener, Ont., this past June during a pretrial hearing for one of her clients, criminal lawyer Leora Shemesh, who had been charged with perjury and obstruction of justice.

Shemesh has long been a thorn in the side of the Peel Regional Police (PRP) service for her efforts to expose illegal behaviour by officers, including in this case allegations of a $20,000 theft by a Peel constable.

"I have gone after them," says Shemesh, "and I don't think they like it." Within the criminal bar, the charges against the lawyer were widely seen as vengeance by the PRP and the Crown's office in Brampton.

Henein's defence, however, managed to expose the dark underbelly of Peel's police force, and those who have tried to bury its many controversies, including claims of racism and allegations that Peel officers too often shoot people without valid cause, steal, assault civilians, lie in court and bungle major investigations, and then go unpunished.

The case joined a series of incidents that have led to harsh criticism from city politicians, the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario, victims of police abuses, civil rights activists and police oversight leaders, and provoked the Toronto Star to editorialize last year that "Something is rotten in the Peel Regional Police Service."

At the heart of the matter involving Shemesh was whether Ian Dann, a Peel constable, had stolen a large amount of cash from an alleged drug dealer during a raid on his home. Shemesh had tried to expose what she believed to be a theft, but the PRP and the Crown's Brampton office seemed more interested in going after her than investigating Dann.

Key to Shemesh's defence was the fact that Dann had acknowledged to Crown attorneys he had taken the money, but the Crown seemed uninterested in pursuing the matter.

Back in 2010, Peel's drug squad arrested Ha Tran, a Vietnamese woman, carrying two bags of marijuana worth $244,000 from her home in Mississauga. Dann and two other officers, Steve Roy and Christopher Krause, conducted a search of her house and found a safe. When they opened it, Shemesh says, Tran and two other witnesses saw Dann remove about $20,000 that belonged to Tran's husband, who was also facing drug trafficking charges.

In court this June, Henein interrogated officials from Brampton's Crown office about what they knew of Dann's alleged theft of the cash.

"So (Dann) took the money, whether he took it from the safe or the table, he took money that did not belong to him, right?" Henein asked Robert Johnston, a Crown attorney.

"That is correct," Johnston said.

"And he converted it to another use?"

"That is correct."

"That's his excuse to you for taking the money?" pressed Henein.

"That is correct."

Three years after the raid, Shemesh, now representing Tran in court, raised allegations with Johnston about Dann's removal of the cash and said, in passing, "Nowadays people have nanny-cams" (which turned out not to be true in this case). Johnston left the room convinced that Shemesh had video footage of Dann taking the money. When he confronted Dann, the constable admitted taking money, but claimed he'd given it to Tran to try to recruit her as an informant.

Under Henein's questioning, Johnston acknowledged that Dann had lied to him about the circumstances.

"You were at least entertaining the notion, if not entirely open to the notion, that not only were the officers lying to you with respect to their initial responses?"

"Yes."

"But they could be globally lying to you and could be responsible for, in essence, just an old-fashioned, outright theft?"

"Most definitely. They'd had since 2010...to discuss the matters with each other, and I had no idea what I was dealing with."

"It was in your mind, then...that this could very well be a situation of not Constable Dann's explanation, but, indeed, Ms. Shemesh's explanation that he's pocketing money for his own purposes. He's stealing money, and everything else is a fabrication to protect himself and cover up his crime?"

"Yes."

Dann's claim had an enormous problem: Tran denied being an informant or receiving any money from the officer, and was actually the person accusing Dann of taking the money. There was also scant evidence she had informed for Peel police; Dann had not entered her name in a databank of informants. And even if Dann had given her money belonging to her husband, it could still legally be considered theft.

Dann, Roy and Krause urged Johnston to drop the Tran case, ensuring the officers would not have to testify. By that point in 2013, Dann already had a credibility problem: He and four other drug squad officers, nicknamed the "Peel Five," had been caught lying in court on a previous drug case.

The Crown did drop the charges against Tran and at least four other drug cases involving Dann.

But was Dann ever punished?

Peel's internal affairs office investigated the constable in 2014. He was charged with a Police Services Act (PSA) violation, not for theft but for his failure to properly follow proper confidential informant procedures. This charge was laid after Tran told internal affairs she was never Dann's informant, explains Shemesh. Dann pleaded guilty, was moved out of the drug squad, and today works as a traffic officer out of 22 Division.

During a preliminary hearing into the Shemesh case last year, Dann said under oath, "I know I didn't steal any money." He did not return messages from The Pointer requesting comment.

Instead of pursuing Dann more aggressively, in 2014, the PRP, under orders from Chief Jennifer Evans, went after Shemesh, the whistle-blower in the case. They believed the lawyer had obstructed justice by claiming to possess a nanny cam video (which she had not) showing Dann stealing money, when no such video existed. She was also accused of perjury by stating under oath, when testifying in a separate drug case, that she had never told anyone she had such a video. She was charged in 2015.

Her trial was scheduled to begin this fall, until Henein's questioning in the pretrial hearing in June exposed how the Brampton Crown's office knew about Dann's troubling actions and did little about it.

The charges against Shemesh were withdrawn soon after. The Public Prosecution Service of Canada is investigating the Crown's Brampton office over its role in the Shemesh case.

"It was one of the hardest things I have ever gone through," says Shemesh, who is today burdened with a large legal bill.

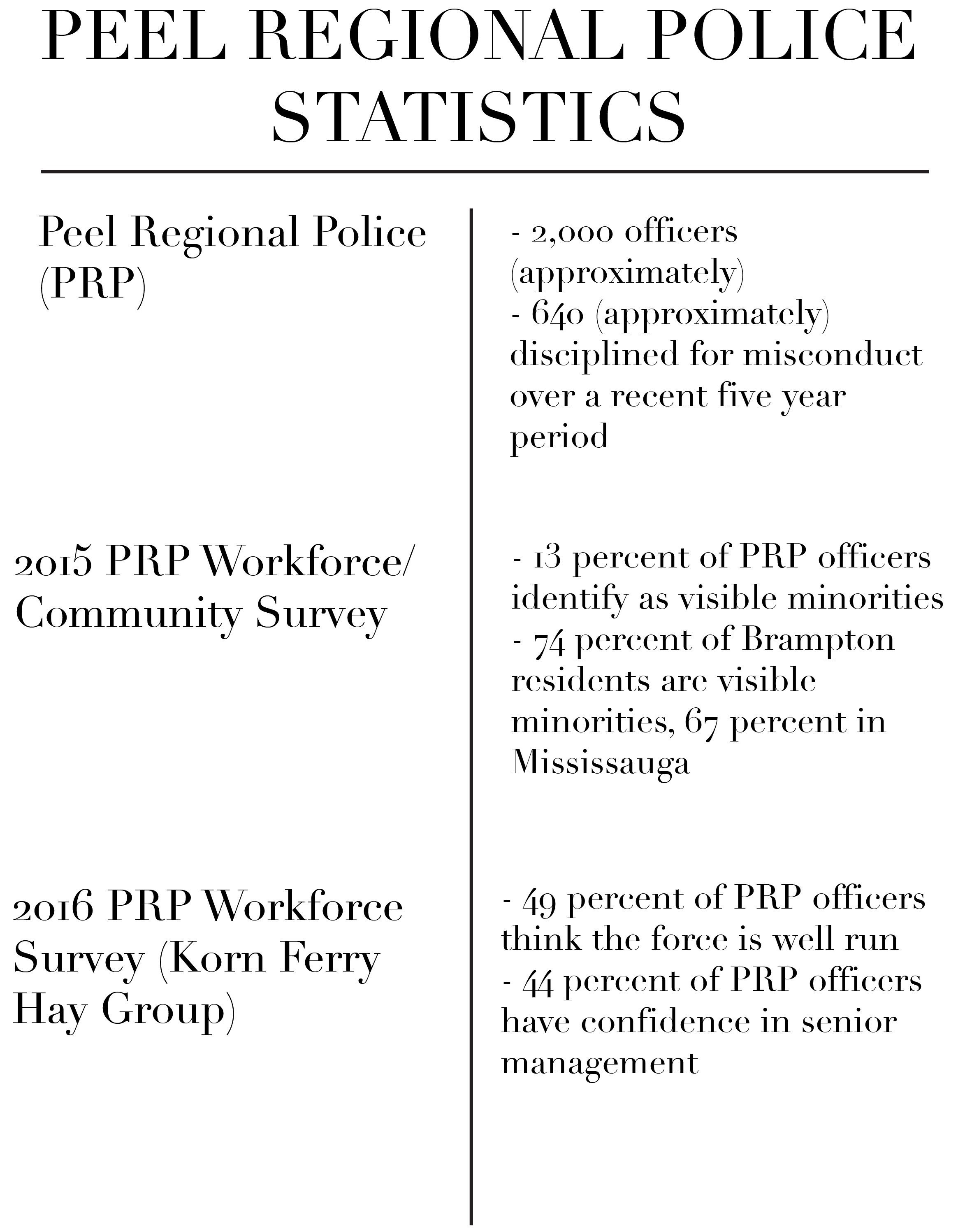

The Dann case was by no means an isolated one. Two years ago, a Star investigation revealed that roughly 640 Peel officers, almost one-third of the force, had been disciplined for misconduct since 2010. This fact came out shortly after Evans' claim that only 2 per cent of the force's officers are disciplined for misconduct. The Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) had roughly the same number of discipline cases during the same period, though it's a force nearly three times the size of Peel's.

In 2011, Ontario Superior Court Justice Douglas Gray stopped a trial after ruling that Peel police vice officers had misled the court, falsifying evidence in a case involving human trafficking and pimping. The charges against the defendant were thrown out, because "the state actors, the police, have been prepared to fabricate a case," Gray wrote in his decision. The actions of the Peel officers who tried to deceive the court were "an affront to decency and fair play," he said.

"It would be difficult to conceive of conduct that would more distinctly shock the conscience of the community than a fabrication of evidence by the police."

A year later, Justice Deena Baltman, of the same court, addressed conduct by Peel drug squad officers in another case that could be described as even more shocking.

"The police lied under oath in order to cover up (an) illegal search and persisted in their lying when confronted with the most damning of evidence," Baltman stated in her reasons for sparing the defendant jail time in a drug trafficking case.

Referring to the attempted cover-up by Peel officers, the judge said, "All these misdeeds were calculated, deliberate and utterly avoidable." Peel officers had "colluded and then committed perjury, en masse," she said, adding: "The police showed contempt not just for the basic rights of every accused but for the sanctity of a courtroom."

Critics of the PRP say problems with the force go to the very top, to Chief Evans. As Andre Marin, former Ombudsman of Ontario and former head of the Special Investigations Unit (SIU), which investigates police-involved injuries and deaths, has said about the Peel force: "The fish rots from the head down."

Evans, who declined to be interviewed for this story, is one of the most polarizing figures in law enforcement, in particular because of her zealous support for carding, a process whereby officers randomly stop members of the public to take down their personal information.

Evans is currently under investigation by the Office of the Independent Police Review Director (OIPRD) over her force's failure to catch a now-convicted murderer who, over a period of years, killed off members of a Mississauga family one by one.

A survey conducted by the Korn Ferry Hay Group in 2016 found only 49 percent of officers agreed that the PRP was well run, and just 44 percent had confidence in senior management. "Peel has always been known as petty and ruthless," says Knia Singh, a Toronto lawyer and civil rights activist.

Just how bad is the Peel Regional Police Service, and is it really, as some victims of police misconduct have claimed, the worst police force in Ontario?

* * *

With 2,000 officers, the PRP is the third-largest municipal police force in the country, after Toronto and Montreal. But in recent years, the conduct of some officers on the force has arguably been comparable to that of an organized crime gang. Consider a small sampling:

Last year, a 30-year veteran of the force, Craig Wattier, pleaded guilty to breach of trust and fraud after watching 241 videos characterized as child porn while on duty, and filing $28,000 worth of overtime to do so. He received a one-year jail sentence.

This spring, a 40-year veteran of the police force, Mark Androlia, was arrested and charged with money laundering and fraud.

In 2012, three off-duty Peel police officers savagely beat a drunk 62-year-old man at a banquet hall after he allegedly touched the breasts of two female Peel officers. The officers dragged him into a bathroom, where they kicked him in the face and broke his nose, leaving him bleeding profusely. Two of the officers were demoted.

In 2015, a Peel officer, Carlton Watson, was sentenced to five years in prison after being convicted on 42 counts of fraud. With a friend, he conspired to file fake accident reports to rip off insurance companies for more than $1 million. Watson was also charged with sexual assault.

In 2013, an 80-year-old Mississauga woman with dementia was tasered twice by three Peel police officers, causing her to fall and break her hip. (She had been holding a knife at the time.)

After a long night of drinking with four other Peel officers one evening in 2011, officer Cody Smith went on a wild ride in his truck on the QEW, swerving all over the road before slamming into a guardrail. He then tried to flee the scene.

In 2010, Sheldon Cook, a Peel constable, was sentenced to more than five years in prison on seven criminal convictions. The RCMP caught him in a sting receiving what he thought was a shipment of cocaine from Peru worth $540,000. Cook was accused of beating up a CFL player, Orlando Bowen, so badly Bowen had to retire from the league.

An instructor, Const. Perry MacVicar, was briefly demoted to a lower pay grade for sexual misconduct after showing female trainees nude photographs of himself and of his erect penis, and then aggressively propositioning the women.

In 2015, criminal lawyer Laura Liscio was arrested by Peel police while standing in a courtroom in Brampton wearing her legal gown, then led outside in handcuffs before being taken to a police station and charged with a drug offence, under accusations she'd smuggled marijuana into the courthouse. The PRP then lied in a press release about the manner of Liscio's arrest, in particular the point that she had been marched out while still wearing her gown. The charges were dropped when it became clear the attorney was not responsible for the pot being smuggled to her client. Liscio is suing the department, seeking $1.5 million.

Of course, all police departments have their share of bad apples and cases of poor policing. And no complete statistical analysis exists comparing the PRP's track record with comparably sized police departments.

There is, however, enough compelling evidence to suggest the PRP has grave and chronic problems. For example, a survey published last year by the Globe and Mail found that Peel police were not investigating 25 percent of sexual assaults reported to them, compared with only 7 percent by the Toronto Police Service. And critics have suggested South Asian crime groups are flourishing in Peel because the PRP does not have sufficient personnel or interest in investigating them.

The problems of the PRP are well illustrated in the shooting death of Marc Ekamba-Boekwa and wounding of Susan Zreik.

One afternoon in March 2015, in a working-class Mississauga subdivision, Boketsu Boekwa came out of her townhouse and began yelling at a neighbour who was sweeping her path, threatening to kill her. Boekwa and her 22-year-old son, Marc, lived together in the townhouse and both suffered from delusions they were victims of a mystical conspiracy. While being restrained by her son, Boekwa threw a knife at the neighbour, which skittered across the ground harmlessly.

The neighbour then called Peel police. Six hours later, three officers showed up, one of whom was a trainee, Jennifer Whyte, a daughter of a (since retired) PRP superintendent, Kim Whyte, a good friend of Chief Evans.

The officers looked at the videotape of the Boekwas' confrontation with the neighbour, footage shot by the neighbour's daughter. The officers then went over and knocked on the Boekwas' door. Marc answered but refused to step out of the house. The officers wanted him and his mother to come out so they could be arrested for uttering threats.

Proper procedure when making an arrest if a suspect refuses to leave their home involves obtaining a warrant and bringing in officers trained for such situations, says Christopher Assie, Boketsu Boekwa's lawyer. Instead, "the lead officer decides to grab (Marc) and pull him out."

In Assie's account, Marc resists and the three officers struggle with him on the ground outside the house, in the dark. One of the officers then exclaims that Marc has stabbed him. Marc breaks free and runs away. At that point, his mother comes out and hits one of the officers on the head with a pot. She is then subdued and put in handcuffs. Marc reappears, brandishing a knife. The officers begin shooting at him,19 bullets in total, 11 of which strike Marc, killing him.

In the melee, Const. Whyte shoots her training officer (who was wearing a bulletproof vest) in the back. Another stray bullet, shot by one of the other officers, passes through a neighbour's window, striking 21-year-old Susan Zreik in the back as she stands in her kitchen.

Assie says the death of Marc and shooting of Zreik could have been avoided if the officers had simply followed proper procedure.

"The police had no right to drag (Marc) out to arrest him," he says. "There was no rush, no need to do things immediately."

When the paramedics arrived, Zreik said, the Peel officers urged them to first attend to the wounded police officer (who was bruised from being shot), and not her, even though she was bleeding from her open bullet wound. Then, when Zreik was at the hospital, Chief Evans paid her a visit.

Zreik happened to be studying policing at a local community college. Zreik's lawyer, Michael Moon, says Evans gave Zreik her business card with her cellphone number. "(Evans) assured her that the implication was that if she went quietly into the night, she could have a career (in policing) going forward."

The next morning, according to Moon, the PRP told Zreik she couldn't go home, but had to go to a local division house and speak to the Special Investigations Unit (SIU), which had been called in to investigate the shooting. This, Moon claims, was a ruse. Moon alleges the PRP prevented Zreik's father from picking her up. Instead, Peel officers drove her to the division house, wearing a hospital gown and with the bullet still in her back. There, Moon says, Zreik was questioned for two hours by a Peel officer, not the independent SIU.

Moon claims the nature of the questions was to clear the PRP of any wrongdoing. "They were trying to convince (Zreik) it was a horrible accident and the police were right in what they did."

Zreik has since launched a lawsuit against Evans and the PRP seeking $21 million in damages, accusing Evans of minimizing her injuries to the SIU in order to question her without the SIU being present. The bullet was in her back for two weeks before it could be removed. Zreik quit her policing studies and suffers from PTSD. Whyte quit as a police officer but still works for the PRP as a civilian employee.

Moon accuses the Peel police of having "a cowboy attitude. And there is no consequence to the officers." The SIU cleared the officers of any wrongdoing in the case.

* * *

Arguably the most controversial aspect of Evans' tenure as chief is her department's record on race relations, a problem underlined by the fact that in 2015 only 13 percent of PRP officers were people of colour, serving a community where 67 percent (about 74 percent in Brampton) are visible minorities.

Last year, Peel's police services board ordered a diversity and equity audit on the force, which is slated for release this November.

The issue of race was highlighted in 2016, when a 6-year-old black girl was handcuffed, both feet and hands, by a Peel police officer while at her Mississauga elementary school. The police had been called because the girl was apparently kicking and punching school administrators. The officers who responded said handcuffing was the only way to subdue her after other efforts had failed. But as the Star editorialized last year, "one thing is clear: A 6-year-old child should never end up in handcuffs."

Allegations of a culture of racism in the PRP were highlighted in the Baljiwan (BJ) Sandu case. Born in India, Sandhu joined the Peel force in 1989 and rose to the rank of detective-sergeant. In 2013, he applied to an internal competition to become an inspector but was turned down. He was told he did not have enough frontline experience.

Sandhu speaks four languages, had worked homicide cases, in intelligence and as a community liaison, and had 872 hours as an acting inspector. He'd received numerous awards and accommodations, including a Queen's Diamond Jubilee Medal for dedication to public service in 2012.

Sandhu submitted a complaint to the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario, claiming he'd been denied an opportunity for promotion due to racial discrimination. His complaint detailed many instances of enduring racial slurs and stereotypes. One example: "Once, I walked into the gym at Headquarters full of officers, one of whom shouted: "Hey, no one called a cab!'" The room, he said, erupted with laughter.

Last year, the tribunal ruled that Sandhu's failure to receive a chance at promotion was, in part, due to his ethnicity. "And as such I find that the applicant has been subject to discrimination because of race, ancestry, place of origin, and ethnic origin in violation of...the [Human Rights] Code," wrote Bruce Best, a vice-chair of the tribunal.

The tribunal's findings further noted that policing portfolios focussed on the large South Asian community are "generally devalued in the service" because they are "associated with the South Asian population" and are "not considered real police work" by the force.

Sandhu has been on stress leave since 2014 and suffers from depression. He recently reached a financial settlement with the PRP.

After the ruling, Evans issued no apology to Sandhu, but did release a video statement assuring the public that promotional practices had changed since 2013 and the circumstances of Sandhu's case were "not reflective of the force's values."

These assurances may be belied by Evans' actions involving another South Asian officer who testified on Sandhu's behalf, Inspector Raj Biring. During Sandhu's human rights tribunal hearings in 2015-2016, Biring seconded Sandhu's contention that racism was a problem within the PRP.

Soon afterwards, Evans ordered an investigation-which was carried out by the OPP, after a police applicant complained about being rejected by the inspector.

The candidate, a Sikh Canadian, claimed Biring, who is also Sikh, had used a racial epithet during his interview. Biring's lawyer, Asha James, says her client rejected the applicant because he was not forthcoming about his family's ties to possible criminals, and Biring used the racial epithet to illustrate how some members of the South Asian community negatively, and unfairly, view South Asian police officers. After the OPP investigation, Police Services Act charges were laid and Evans ordered a hearing into the complaint, which is ongoing.

"There are a lot of irregularities in the way the complaint was processed," James says with respect to Evans' involvement.

* * *

The most contentious issue dogging the PRP on race has been Evans' steadfast support of the "street check" process colloquially known as carding. Carding occurs when police stop people on the streets for no other reason than wanting to document their name, ethnicity and other information. Critics say carding, in the absence of a direct investigation of a crime, is a clear violation of prohibitions in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms against arbitrary detention.

In Peel, where 15 percent of the population is black, the force's own data showed that on average almost 25 percent of those being carded were African-Canadians. Between 2009 and 2014, Peel police conducted 159,303 carding checks, with black people as much as three times more likely than white people to be stopped in a given year. Peel police have "a terrible reputation in the black community," says civil rights activist and journalist Desmond Cole, "and they have caused it themselves."

In 2015, the police services board voted to direct the PRP to suspend carding. Evans refused to comply, arguing the board could not direct her on operational procedures, bringing in a legal opinion without previously informing the board ahead of the meeting. (Her claim was later rebutted by legal experts who stated carding was a policy issue under the board's authority, not an operational issue.)

The force amended its carding practice only in 2017, after the Ontario government curtailed it. But earlier this year, Evans complained that not being able to card had led to a spike in violence in Peel, without furnishing evidence connecting the two issues.

More troubling news about carding emerged after the death of Jermaine Carby.

In September 2014, Carby, a 33-year-old black man, was riding in a car driven by an acquaintance when a Peel police officer signalled the driver to pull over, apparently because he noticed a licence plate was loose. Carby had outstanding warrants from British Columbia and a criminal record, as well as a history of violence and mental health issues.

The officer checked out the driver's credentials but also decided to demand Carby's personal information, something not legally required of passengers during a traffic stop.

"This was a traffic stop that turned into a carding scenario," insists Faisal Mirza, a lawyer who represented the Carby family at his inquest.

When the Peel officer checked him out, he discovered Carby's parole violation. By this time, another police car had arrived, with two more officers. They asked Carby to step out of the vehicle, which he did. A shouting match ensued. The police later claimed Carby pulled out a knife and came toward them. After he refused to drop it, Const. Ryan Reid shot seven times; three bullets struck Carby, killing him.

When the SIU showed up to investigate the shooting, the knife Carby allegedly had been holding was missing from the scene. Standard procedure at crime scenes is that evidence is never removed. Yet the Peel officers did exactly that, handing over the knife hours later to the SIU. "This conduct is hard to fathom," the SIU noted in its report on the shooting.

La Tanya Grant, Carby's cousin, believes the knife was planted by police. She notes his fingerprints weren't found on the knife, though it did have his DNA on it. "It was a kitchen knife, a serrated kitchen knife. No one walks around with that type of knife."

At the 2016 inquest into Carby's case, eyewitnesses gave conflicting accounts as to whether the knife existed. The driver of the vehicle testified Carby did have it, as did some other eyewitnesses, while others said they didn't see one. In the end, the officers were cleared of wrongdoing. "I do think race was a factor" in Carby's death, Mirza says.

Carby's family has since launched a lawsuit against the PRP alleging racial profiling and seeking $12 million, with La Tanya Grant voicing her opinion of the PRP that "it's the worst police force in all of Ontario."

Next: Bungling major investigations. Accusing innocent people of crimes they clearly didn't commit. Lying in court. And all without punishment. What's being done to bring Peel police to heel?

Submit a correction about this story