Who’s telling the truth in a $28M lawsuit hanging over Brampton?

(This is the first in a series of articles The Pointer will be publishing, detailing the trial in the Inzola Group's lawsuit against the City of Brampton)

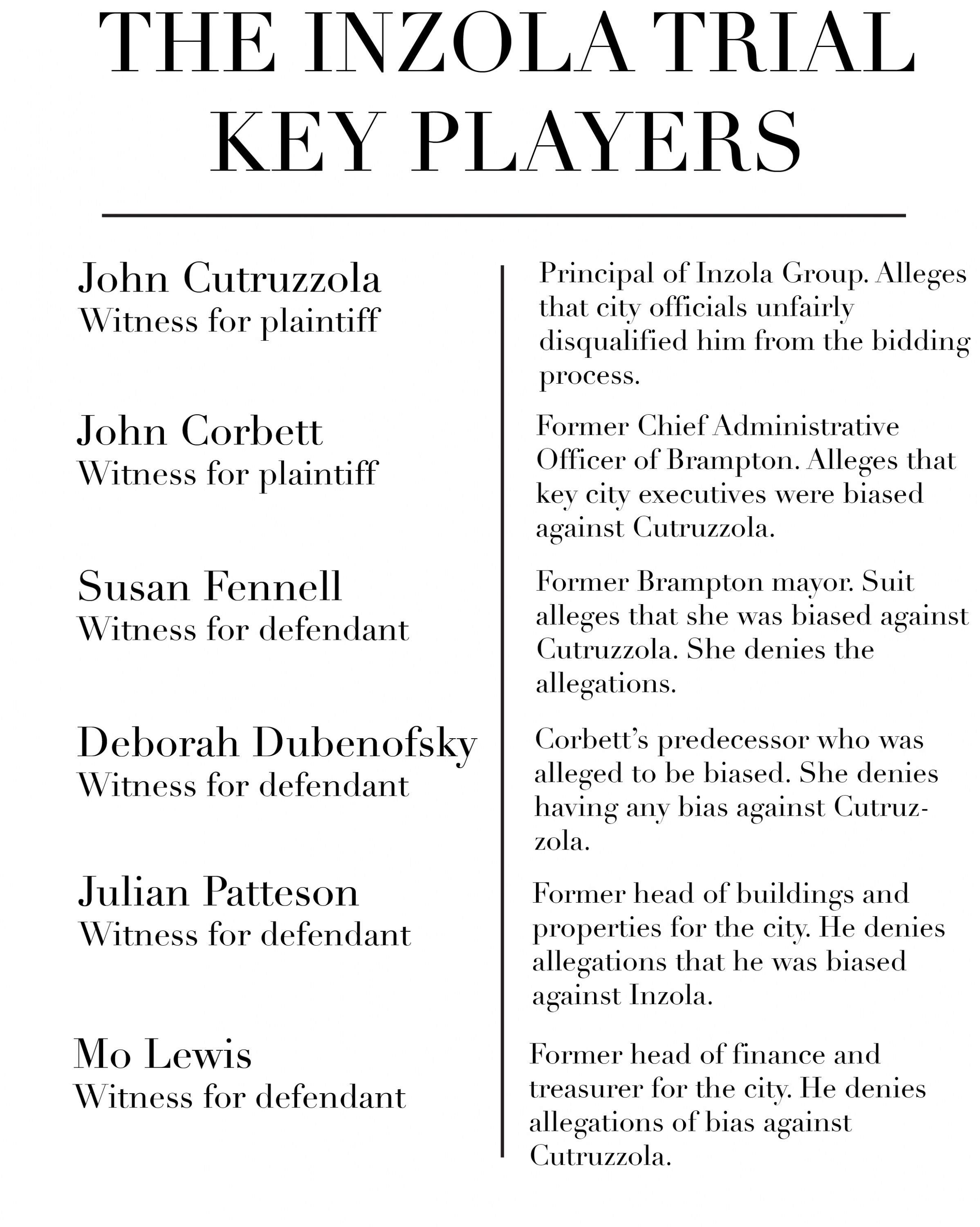

Four former city hall executives, once responsible for running Canada's ninth largest municipality, took the witness stand in an Orangeville courtroom this June to testify in a local builder's $28.5-million lawsuit against the City of Brampton that alleges misconduct by senior staff. Among them was the key accuser in the case, former chief administrative officer John Corbett.

Four former city hall executives, once responsible for running Canada's ninth largest municipality, took the witness stand in an Orangeville courtroom this June to testify in a local builder's $28.5-million lawsuit against the City of Brampton that alleges misconduct by senior staff. Among them was the key accuser in the case, former chief administrative officer John Corbett.

As the suit nears a verdict after an eight-week trial and seven years of grinding through the legal system, taxpayers will soon learn whether a landmark $500-million development deal to revitalize Brampton's aging city centre was awarded unfairly by former bureaucrats, who gave contradicting evidence at trial.

The man whose company finished construction of Brampton's downtown City Hall in the early '90s, John Cutruzzola, launched the case in 2011 after Inzola Group had been disqualified, a year earlier, from the bidding process to build a city hall extension and other projects designed to transform the city's historic Main Street area.

The suit alleges that senior staff and then-mayor Susan Fennell did not want the company to succeed in the competition, which used a procurement process called "competitive dialogue" that had never been tried in Canada before and attracted only three bidders for one of the largest projects in Brampton's history.

The City of Brampton and Fennell have denied the allegations in the lawsuit.

Two former Brampton executives, ex-city manager Deborah Dubenofsky and Julian Patteson, who was in charge of buildings and property, denied that any bias against Inzola entered into deliberations by senior staff who held closed-door meetings in 2010 and 2011, when the decision on a preferred bidder dominated the city's business.

Mo Lewis, the former head of finance and city treasurer, testified that Dubenofsky and Patteson had conducted themselves unprofessionally toward Cutruzzola in closed-door meetings, but denied the central allegations in the lawsuit.

Corbett provided damning testimony that directly contradicted the other three.

Documents entered as evidence by the plaintiff also suggest a different interpretation of some of the key testimony.

The hearings, after witness examinations wrapped up near the end of June, will continue the second week of September for closing arguments.

Brampton City Council eventually approved the choice of a developer made by senior staff, and successful bidder Dominus Construction built a $205-million city hall extension, a price tens of millions of dollars higher than what Inzola had proposed in its disqualified bid, which the city tried unsuccessfully to prevent the company from ever revealing. (The project's other two phases, including a downtown library, never went forward.)

There are no allegations in the lawsuit of any wrongdoing by Dominus, which has always maintained it followed all rules of the procurement process. Dominus principal Joseph Cordiano testified in court that the entire project was carried out following all of the contract rules.

David Chernos, representing Inzola Group in the lawsuit, began his methodical cross-examinations with thousands of pages of documents the city was compelled by the court to produce in hand.

One day in June, he rose to question a central figure in the case: Deborah Dubenofsky, who was overseeing an entire administration of about 2,700 staff when the massive deal became her top priority.

"You know that a key issue (in the lawsuit) is your involvement?" Chernos asked, staring her directly in the eyes.

"Yes," she responded, just above a whisper.

"You made negative remarks about John Cutruzzola," Chernos suggested to Dubenofsky, referring to meetings with senior staff when the selection process for the downtown deal was discussed, before and after the final council decision in 2011. He asked if she recalled making such comments.

"I do not," she answered.

Chernos pressed on. "If other members of the senior management team recall you making negative comments of Mr. Cutruzzola, they were wrong?"

"They would have to be," she said, as Justice John Sproat of the Ontario Superior Court looked on.

The unflappable judge, who attentively wrote notes throughout the complex trial in May and June, has handled some of Brampton's largest cases since being appointed to the bench in 2003.

Days before Dubenofsky took the stand, the court heard the testimony of John Corbett, who replaced her as the city's chief administrative officer in 2012, after council decided not to offer her another contract. The trial revealed that some members of council felt Dubenofsky was too close to Fennell. During her testimony, Dubenofsky called that characterization "unwarranted."

Corbett, the plaintiff's key witness, described Dubenofsky's relationship with Fennell as being focused on "carrying out the mayor's agenda, at times contrary to council's wishes and without council's knowledge". Dubenofsky denied the allegation. Fennell testified that Dubenofsky was fastidious in representing all of council evenly.

Corbett was asked about Dubenofsky's views of Cutruzzola that he witnessed her expressing during closed-door meetings with senior managers.

He said she "commonly expressed" routine comments about the developer that were "affronts to his character, personality and physical stature (Cutruzzola is slightly taller than five feet) mimicking his personality as being egocentric, his stature, his Italian accent, his youth in Italy." Corbett said such comments were "commonly expressed" by Dubenofsky.

Corbett testified that such comments were made routinely in front of senior staff by Dubenofsky, and to a lesser extent by Julian Patteson, the former head of public services, who once ran the city's buildings and property department, and Mo Lewis, the former treasurer and head of finance. All three denied his allegations.

During his cross-examination, Adam Stephens, one of the lawyers representing the city, suggested Corbett had a "personal animus" toward Dubenofsky because she tried to fire him, prior to council's decision to hire Corbett for her job.

Corbett denied the assertion. "That's part of the territory," he replied. "No. I'm a big boy. I've been in senior positions most of my adult career. I hold no grudges or animosity. You're hired to be fired, just as you said," Corbett testified, referring to a comment Stephens had made earlier.

During his chief examination, Corbett continued to provide damning evidence against the city's case, describing one meeting when Patteson got down on his knees in an effort to mock Cutruzzola's short stature while mimicking his Italian accent. Patteson denied the allegation.

"Through their predisposition toward Mr. Cutruzzola's personality, in my view, it would be impossible for them to be objective," Corbett said, describing the behaviour of Dubenofsky, Patteson and Lewis. "It would be impossible for Mr. Cutruzzola's proposal to be dealt with fairly."

All four of the former executives no longer work for the city.

Patteson was vice-chair of the selection committee and Lewis was chair. They, along with four other members of the committee, including Corbett, were the only people allowed to evaluate the full bids and were supposed to independently make a recommendation for one preferred respondent (bidder) to council.

Dubenofsky was not on the committee.

Council was told by senior staff that under the particular procurement process being used, a method they had selected, that the city's elected officials were not allowed to see the bids. (Inzola challenged this claim by staff, arguing during trial that the procurement contract contained no rule preventing council from seeing the bid proposals.)

Dubenofsky was not on the committee, was not supposed to see the bids and was not to have any involvement in the decision-making process, other than to manage reporting and timelines for council so it remained informed of key milestones.

Patteson has been the principal witness for the municipality since the lawsuit was launched in July 2011, providing sworn testimony and affidavits, and representing the city's defence throughout the pre-trial discovery process, when each side is allowed to probe the other for evidence to help their case.

During the trial, Patteson was asked by Stephens about the main allegation in the lawsuit: that he and other senior staff were biased against Cutruzzola.

"I have no bias toward Mr. Cutruzzola," Patteson testified.

During cross-examination, Chernos put to Patteson that he, Dubenofsky and Lewis ridiculed the builder while he was in competition for the downtown deal. Patteson denied the allegation.

Chernos showed him a copy of an email Patteson had sent to Dubenofsky, obtained through the lawsuit. In it, Cutruzzola's upbringing in Italy is mocked by Patteson, who wrote to the city manager: "I ran through the village."

"Yes, I thought it was fun poking fun at him," Patteson responded.

Chernos asked: Were the negative comments made behind Cutruzzola's back?

"Yes, he wasn't there," Patteson replied, saying it was just "good-natured ribbing."

"Ribbing, you do in public; you did it behind his back," Chernos said. "You knew that if you said these things in public you could not be seen as objective in the (selection process)."

"No, that's not right," Patteson quickly replied, shaking his head.

When Lewis took the stand days later, he was cross-examined by Stuart Svonkin, one of Inzola's lawyers.

"At senior management team (meetings) people made negative comments about John Cutruzzola?" Lewis was asked.

"Yes," he replied.

"Was Deborah Dubenofsky one who made negative comments?"

"Yes."

"Unprofessional comments?"

"Yes."

Lewis testified that Dubenofsky and Patteson, in closed-door meetings with senior staff during the period they were to decide on a preferred bidder, disparaged Cutruzzola, made fun of his "ego" and mocked stories he had told about his childhood in Italy.

He was asked if he made any negative comments about Cutruzzola in the meetings.

Lewis said he had expressed frustration about dealing with Cutruzzola during the procurement process. "We are human."

Another central issue in the litigation is the role played by Dubenofsky, who was only supposed to handle agenda management for the procurement, not be involved in decision-making.

Corbett testified that her actions went "far beyond" agenda management, alleging that she controlled much of the decision-making process and was heavily involved in the re-drafting of reports that provided direction and recommendations to council, even though she was supposed to play no such role.

For a pre-trial motion in 2016, Dubenofsky testified under oath that she only dealt with the final versions of such reports, to ensure brevity.

Chernos read her 2016 transcript back to her, then presented the court with documents, obtained from the city after it was compelled to produce them, that appear to contradict her original testimony.

"You said: 'I would see the very final, last draft, the very last draft, that's correct.' But that's not correct, is it?" he said, his voice growing louder.

"No, it is not," Dubenofsky responded, her voice cracking as she acknowledged providing misleading testimony under oath.

"Your evidence was not true."

"I concede there were inaccurate statements," she said. "I was incorrect."

Chernos continued his aggressive line of questioning.

He said her admission that she had dealt with early versions of the reports "is directly contradictory to what you testified to in 2016, isn't it?"

"Yes," she responded.

Chernos repeated her evidence from 2016, showing more documents the city was compelled to produce under court order that contradict what she had originally testified to. Dubenofsky repeatedly responded that she was "incorrect," eventually stating that in 2016 she had relied on a "faulty" memory.

Chernos then took Dubenofsky back to her 2016 testimony, regarding the role she played in handling what were supposed to be the independent reports of external "fairness advisor" James McKellar, who was hired by council members to report directly to them about his oversight of the selection committee, to ensure the procurement process was carried out fairly by senior staff.

The trial heard that McKellar was the same person Patteson had originally recommended the city hire to help design the "competitive dialogue" procurement process for the deal, which he has promoted around the world. Patteson testified that he had met McKellar years earlier, through conferences and organizations related to municipal real estate.

Inzola's lawyers probed whether the overlap of McKellar's roles, between design of the process and accountability for how it was carried out, represented a possible conflict of interest. The lawyers questioned how he could properly hold accountable both his own recommended method (which the city paid him to help create) and the staff using his method, staff who had selected him for both roles.

Dozens of documents entered as evidence by the plaintiff (documents the city, after pre-trial motions, was ordered by the court to produce) suggest staff were heavily involved in the drafting and re-drafting of McKellar's reports, which were supposed to go directly from him to council.

Reading from transcripts, Chernos twice repeated what Dubenofsky said under oath in 2016, regarding the fairness advisor's reports: "You didn't have to involve yourself at all, no review of drafts (of McKellar's ostensibly independent reports), even final drafts."

"That testimony you gave was also untrue, wasn't it?" he asked her.

When Dubenofsky said, under oath in 2016, that she had "no involvement" in drafting what were supposed to be independent reports to council, "You weren't correct," Chernos put to her.

"Yes, it was incorrect," Dubenofsky replied.

The decision to disqualify Inzola from the bidding competition in 2010, and whether Dubenofsky was involved in that decision, is another central issue in the lawsuit.

"I asked you about this in 2016," Chernos said to Dubenofsky, continuing on the same course. He presented more city documents produced under court order for the litigation.

Dubenofsky, according to the transcript of her 2016 testimony, had said she "found out when the public found out" about one of the issues that led to Inzola's disqualification, Chernos repeated. "No more involvement than the public, that was your evidence, correct? That was just flatly untrue, wasn't it?"

"It was incorrect," Dubenofsky replied.

Documents entered as evidence suggest that, contrary to her 2016 testimony, she was aware of the disqualification issue from the beginning and directed staff to keep her closely informed.

The documents do not indicate Dubenofsky was responsible for making decisions regarding what led to the disqualification, or the ultimate decision to remove Inzola from the competition.

Corbett had earlier testified that he witnessed Dubenofsky, in meetings with the senior management team, express her desire that Inzola be disqualified.

"That was Deborah Dubenofsky's desired outcome," Corbett stated. "Everyone in that troika (Dubenofsky, Patteson and Lewis) shared the same view and opinion." All three denied the allegation.

He testified that though the rules did not allow Dubenofsky to exercise any influence over the decision to award the historic downtown deal, he witnessed her directing much of the decision-making process.

For the same 2016 pre-trial motion in the case, a written statement of Corbett's evidence was provided, which he said, under oath during his deposition for the motion, is accurate.

In it, Corbett states, "notwithstanding that she was not on the Steering (selection) Committee, Ms. Dubenofsky was involved in virtually every important aspect of the (downtown) RFP process and had input and influence over every significant decision made by the Steering Committee...Together with Messrs. Patteson and Lewis, she was involved in directing virtually every aspect of the process, including the disqualification of Inzola."

Dubenofsky denied the allegations, testifying that her role and actions did not go beyond "agenda management" for the process. Patteson also denied the allegations. Lewis denied Dubenofsky was involved in decision-making.

Corbett testified that he witnessed Dubenofsky directing members of the selection committee as to which bidder should be awarded the deal.

"It was understood from Deborah Dubenofsky's dialogue that it was very critical that Dominus would become the preferred vendor for that project," Corbett said.

City documents shown to the court included a draft report by the selection committee that indicates Dubenofsky knew Dominus would be selected by senior staff seven weeks before the recommendation went to council for a vote. Emails also presented in court suggest she worked with Fennell, prior to the council decision, to garner support for the Dominus recommendation.

In his written statement for the pre-trial motion, Corbett describes what he alleges to have witnessed, that "Dubenofsky was carrying out a political agenda on behalf of Mayor Fennell. It was clear to me (and I believe to the other senior members of City staff) that Mayor Fennell favoured a result in the (downtown) RFP process that did not involve Inzola ... and ideally saw the project being awarded to Dominus. From my observations of her involvement, Ms. Dubenofsky furthered that objective."

Fennell, who testified in June, has always denied Corbett's allegations or that she had any bias against Inzola or favouritism toward Dominus, which was awarded the contract in the summer of 2011.

Dubenofsky, also denied the allegations. She, Patteson and Lewis denied the allegation that they wanted Inzola to be disqualified. The city maintains that it carried out a fair, impartial procurement process. Dubenofsky further denied the characterization of her relationship with Fennell presented in court and testified that she never gave direction to select Dominus.

Fennell also denied any bias against Inzola and any favouritism toward Dominus, which was awarded the contract in the summer of 2011.

During his examination by Chernos, Corbett was shown a portion of the original draft for minutes of a selection committee meeting held on March 31, 2011, three days after the March 28, 2011 vote by council to provisionally accept the committee's recommendation to award the contract to Dominus.

Inzola obtained the original minutes through the lawsuit.

In a section of the draft minutes, which was later removed and no longer appears in the final version, it states, "council sent a message to the community that Inzola is not the big guy in this town anymore."

Corbett was asked if he recalled who made the statement at the March 31, 2011 meeting of the selection committee, days after council approved Dominus as the preferred bidder.

"Yes, I do," he testified. "Mr. Mo Lewis."

The court was shown that the draft minutes, with the comment included, were originally circulated for review and approval to senior staff who had attended the selection committee meeting. At that time, which was prior to the filing of the Inzola lawsuit, no revisions were requested.

After the lawsuit was filed in July of 2011, the following month Lewis sent an email to the minute-taker, Sandra McCullough. The email was entered as evidence in the case. It states, "Sandra: In these minutes, you need to delete the sentence re the debrief of the March 28th [council] meeting, that says, "Council sent as (sic) message to the community that Inzola is not the big guy in this town anymore.'"

Chernos asked if Corbett had ever seen the email from Lewis instructing that the minutes be altered, telling the court, "the city, in fact, produced a copy of these minutes for this litigation with the comment by Mr. Lewis gone."

Corbett testified that he had not seen the email before.

"Were you involved in removing those comments?" Chernos asked.

"No, not whatsoever," Corbett answered.

McCullough provided a pre-trial written undertaking for the case, stating that if words appeared in original versions of the selection committee meeting minutes, they must have been said.

Stephens asked if Patteson recalled seeing the draft of the minutes with the comment about Inzola not being the "big guy in this town anymore", made days after council accepted the selection committee's decision to partner with Dominus.

"Yes," Patteson replied.

"What was your reaction?" Stephens asked.

"That amendments were required", Patteson replied. He testified that he told the minute-taker, "I didn't hear this, it's not professional. It should be removed."

Under cross-examination, Chernos pressed Patteson about the comment made in the meeting, according to the original minutes, reminding him that McCullough had stated, that the words in minutes she took, were in fact said.

"I don't recall anyone saying that or anything like that," Patteson testified.

Chernos continued the same line of questioning.

"I'm putting to you that Mo Lewis said those words."

"I don't recall anyone saying those words," Patteson responded.

There is no record before the court of a request to correct the minutes when they were first circulated for review to Patteson, Lewis and other senior staff, prior to the filing of the lawsuit.

Lewis took the witness stand after Patteson. He was shown the original minutes of the March 31, 2011, selection committee meeting and asked by Stephens about the comment that Inzola was not the "big guy in this town anymore".

"That statement was made by me," Lewis testified, to several gasps of surprise in the courtroom.

Stephens asked him about his email to McCullough, five months after the meeting, and after the lawsuit was filed, instructing her to remove the comment from the official minutes.

The comment was "not intended as part of our day-to-day minuted-items," Lewis explained. He testified that the comment was made to "instill confidence" in staff that council had made a decision and that the committee could move forward with its work.

During the trial, Inzola's lawyers argued that the central allegation of bias against the company by senior city staff and Fennell, is supported within the city's own 2013 statement of defence and the subsequent actions of officials who directed the city's strategy in the case.

Two months before the trial began, the city removed from its filed statement of defence damning allegations accusing Cutruzzola, without any supporting evidence, of political influence and corruption. The statement accused Cutruzzola of a range of unsubstantiated behaviour, claiming he was used to doing business in questionable ways.

These allegations had remained on the public record for more than four years, despite repeated pre-trial requests by Inzola to either provide any evidence to substantiate the claims, or remove them.

Prior to withdrawing the allegations, the city's filed statement of defence accused Cutruzzola of a range of unsubstantiated behaviour, claiming he was used to doing business in questionable ways.

Chernos pressed Patteson, during his cross-examination, about how the damaging allegations came about.

"Were you involved with instructing outside counsel for this litigation?" Chernos asked, referring to the lawyers who have represented the city.

"I don't know who it was," Patteson replied.

"You were the main witness in discovery, you swore affidavits, and you don't know who gave instruction to outside legal counsel (for the allegations in the 2013 statement of defence)?" Chernos said.

Chernos appeared to lose his patience. He made it clear that the unsubstantiated accusations were being taken very seriously by his client.

"Inzola asked (during the discovery process) for how the allegations were reached. The city said there were no facts to back up those allegations. They were not withdrawn until five years later, March this year," he said. Chernos waited for a response, looking directly at Patteson, who kept his head cast down, and remained silent.

Chernos continued. "Who instructed outside counsel to make these claims and then refuse to withdraw them, even though they could provide no evidence to back the claims?"

Chernos demanded that Patteson respond.

Stephens, the lawyer representing the city, who was not one of the lawyers representing the municipality when its hurtful allegations against Cutruzzola were made in 2013, interjected.

"The witness answered: he didn't know."

Submit a correction about this story