How many people should be allowed to live in one house?

Major Singh, an architect by trade, settled in Brampton in 1987 at 32, after escaping bloody anti-Sikh violence in Delhi, India that targeted turbaned men like him. He has called this city home ever since.

His experience in Delhi was not what one might expect in 1984, he recalls. "I myself was brick-batted and stoned."

After living briefly with a sister who had already settled in Brampton, he moved out to build a life in a place of his own, starting his solo adventure in an oft-maligned style of housing: a basement apartment. Sometimes known as secondary units, such apartments, tucked away in single-family home neighbourhoods, are at the heart of one of the city's most divisive issues.

His personal experience, having depended on such housing, is one reason Singh has become a passionate advocate for reforming zoning bylaws to ensure more units of this type are available legally. Others in the city would like to see bylaws toughened in hopes of curtailing the practice. It's widely believed many landlords maintain such units outside the regulatory and licensing framework.

Recently, for a Forum Research survey commissioned by The Pointer, 999 Bramptonians were asked what they thought about secondary suites. Some 47 percent said they thought homeowners should be allowed to have secondary suites in their homes. Countering that, 33 percent said the city should not allow secondary suites, while 20 percent weren't sure.

Ontario's Strong Communities through Affordable Housing Act was amended six years ago, mandating that all municipalities in the province allow legal secondary suites. The legislation came into effect in 2012, but the province allowed cities a few years to work out their own rules and licensing to accommodate this alternative form of affordable housing stock.

Brampton brought in its new rules in 2015. According to the city's bylaw enforcement department, "the number of illegal secondary unit complaints increased from 861 in 2016 to 1,271 as of July 31 this year. That's a spike of 48 percent within two years. As of early last year, the city reported that only 661 registrations had been submitted for secondary suites, and of those only 141 had been completed.

Despite numerous publicly stated estimates for the number of overall secondary suites in the city, many of which are probably not properly registered, the city says there is no way to quantify how many of these units actually exist.

According to Brampton's 2016 census profile, the municipality has the highest average number of people per household in the Greater Toronto Area, and one of the highest numbers for any large city in the country. Brampton households had an average of 3.5 residents, compared with a national average of 2.4 and an Ontario average of 2.6. That means the average Brampton household has 46 percent more people living in it than the average Canadian home.

Some 42,060 Brampton residential units house five or more people. It's the only municipality in the GTA where this census category outnumbers all the others, and a sharp contrast to Toronto, where one-person households are the largest category. The large household size suggests there is a high demand for secondary suites in Brampton.

"This is an issue that really concerns me," Ward 7 and 8 Regional Councillor Gael Miles said during a May 2017 council committee meeting. "The fact that we have many, many properties in the city that are converting single-family homes to multi-family residences." Miles said at the time she was aware of many single-family homes that were being converted to house three or more separate units.

Miles was citing the common practice of using secondary suites to house multiple extended families, usually members of the same clan, within a house. It's an issue many perceive to be somewhat unique to Brampton, and problematic.

Asked in The Pointer's poll whether secondary suites represent a burden to city services, 44 percent agreed, while 26 percent said they don't, and 30 percent weren't sure. (The poll, conducted by Forum Research over the last two weeks of August, has a margin of error of plus or minus three percent.)

City officials suggest the practice does put a significant strain on municipal service delivery. For municipal finance officials, housing so many people at one address becomes an issue because property taxes are the same regardless of the number of occupants, while a large multi-generational household uses a higher than average share of city services and infrastructure.

Brampton's director of bylaw enforcement, Paul Morrison, says the city anticipates services on a particular level of need per housing unit. "So waste consumption, water consumption, hydro consumption, garbage being put out-, all those are considered for single-family use. If you double or increase [household size] by 20 or 40 percent, that is a strain on services."

Driveways filled with a fleet of cars are a common sight in the city's suburban neighbourhoods, with parking pads often extended to provide even more space.

Household sizes are regulated by the City of Brampton's Occupancy Standards Bylaw, which stipulates that "the maximum number of occupants in a dwelling unit shall not exceed one person for each 14 sq. m (150 square feet) of the total floor area." It further restricts habitation by putting a cap on occupancy of bedrooms, stating that no room shall be used for sleeping purposes unless it has a minimum width of 1.83 metres (6 feet); a floor area of at least 5.6 square metres (60 square feet), and further, that a room in which two or more people sleep needs a floor area of at least 3.7 square metres (40 square feet) for each person.

Anthony Bakker, much like Singh, has had a decades-long relationship with this community. He was born in 1964 in Bramalea, 10 years before an amalgamation created today's City of Brampton. He works as a shipper-receiver in Mississauga. Bakker's awareness of local history and sense of civic pride are as infectious as a good belly laugh. With a finger firmly on the pulse of the city, Bakker knows every issue dogging Brampton inside and out, and that includes secondary units.

He says he has no problem with multigenerational households and secondary suites themselves, as long as the property is maintained and no unreasonable change to infrastructure is made.

"To me, (the problem occurs) when you have situations where the homeowner, or owners, are making changes to the property that negatively impact [their] neighbours; when you take your front lawn and cut it in half because you're paving over half of it," Bakker says.

Conversations about the issue, inevitably, have to acknowledge the elephant in the room. Bakker reflects on a well-known perception among long-time Bramptonians that South Asian immigrants are the residents most likely to live in such households and that, overall, they're a drain on the city.

That perception has taken root in a city undergoing a cultural sea change. "White flight," a phenomenon more closely associated with U.S. cities a few decades ago, and more recently in parts of Europe, has been occurring in Brampton since at least 2001. While the visible-minority and Indigenous population of Brampton increased by 330 percent between 2001 and 2016, the white population decreased by 25.5 percent. In raw numbers, 39,285 fewer white people were living in Brampton as of 2016, compared to 2001.

However, Brampton's visible-minorities, many of whom rely on secondary suites just like generations of Irish and Italians and Portuguese immigrants before them, do not see themselves reflected in their local government. Of the 11 city council positions, including the mayor, only one councillor is a member of a visible-minority group, Ward 9 and 10 Councillor Gurpreet Dhillon. It's a disparity that occasionally contributes to the cultural alienation felt in the city.

In July 2017, fellow Regional Councillor John Sprovieri received an email from a citizen with the subject line, "Why are WHITE PEOPLE still planning Brampton's future?" To which he responded, controversially, in emailed comments later circulated by the recipient on Facebook, that white people had created a welcoming land of equality. "I hope that the newcomers will learn the values of the white people so that Brampton and Canada will continue to be a favourite destination for people who want a better and peaceful lifestyle."

Sprovieri, a 30-year veteran on council, quickly retracted the remark, explaining that he didn't mean to use the term "white people." What he meant, he said, was that newcomers should appreciate "Canadian values." But it was too late. Brampton residents responded on message boards and social media and pointed out some of the biggest scourges created by immigrants were secondary suites: piled-up cars, overflowing garbage containers and school portables that, critics claimed, were a result of an influx of home-dwellers who don't contribute to the property-tax base.

Bakker, whose parents immigrated to Canada from the Netherlands after the Second World War, is among the Brampton residents who take a welcoming attitude toward newcomers. On message boards such as Reddit, he often finds himself at odds with people who want to blame all the city's woes on immigrants. As a child, he lived in a six-member household, and his parents' struggle to build a life in Canada, it gave Bakker a firsthand insight into the realities of immigrant life.

"It was always the thing with the Italian community that kids would live at home, saving their money until they could afford to go out [on their own]. And so [it's not] an unusual thing as many people would think. The South Asian community isn't the only culture that has that kind of ethos to it," Bakker says.

The issue isn't just about culture. Brampton's demographic explosion and the subsequent shortage of affordable housing units make multi-family cohabitation a necessity for many newcomers looking to make a life in Canada.

Brampton is experiencing population growth much higher than the provincial and national averages. The city's population grew from 523,906 people in the 2011 census to 593,638 just five years later, an explosive 13.3 percent increase, in contrast to a provincial average of 4.6 percent and the national average of 3.17 percent. Between 2001 and 2016 the city's population grew by a mind-bending 83 percent.

"I think because of the financial or economic situation, most of the people who come to Toronto or the GTA, they start from the basement and they grow out of it very fast. Now it may be a little difficult because of the way the real estate market is," Major Singh says.

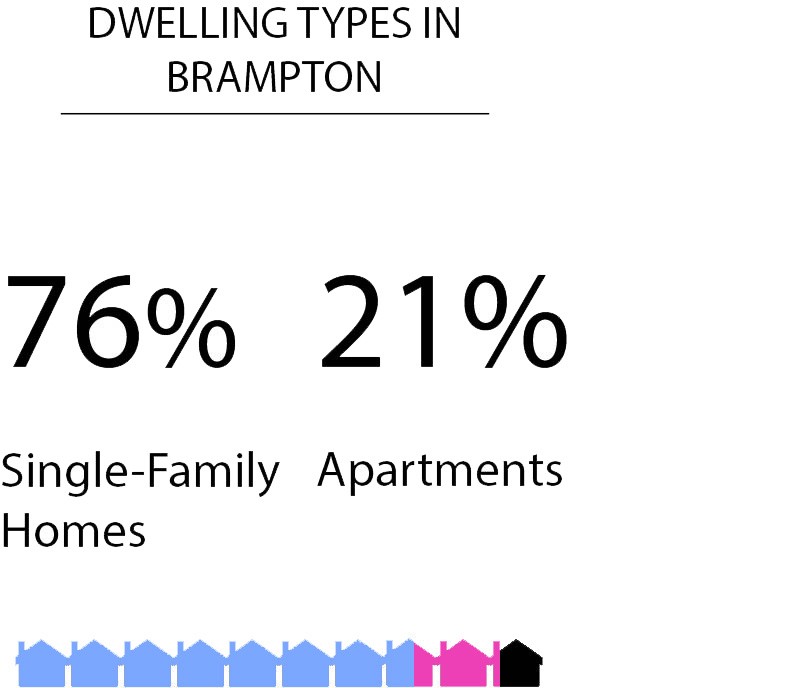

According to the same census profile, there are 173,428 dwellings in Brampton. Of those, 131,255, or roughly 76 percent, are single-family homes. The lack of dense housing such as highrise apartments means there are few alternatives.

Singh wants the government to make it easier for providers of secondary units to meet bylaw and regulation standards and provide a safe living environment for occupants. Many of these units go unregistered with the municipality, rendering the basement apartments unsafe to live in, he says.

"My only concern is that life safety should be given a priority, so to me restricting these things by zoning bylaw will affect people's lifestyle and life safety."

Real estate agent Sukhjot Naroo, who sat on the advisory committee that designed Brampton's 2015 regulations for secondary units, agrees with Singh about the need for zoning reform, but believes unwillingness to register with the city is the result of an intimidating process.

"Instead of helping [owners], they are trying to browbeat them. I thought it could have been better. Instead of having penalty provisions of a $25,000 fine, and this fine and that fine, it could be done much better in a more relaxed way," Naroo says.

Brampton Ward 1 and Regional Councillor Grant Gibson agreed with Naroo in 2016, commenting that, "Part of the problem is we haven't made the process very easy. It is still a very difficult process to go through."

"Usually when you bring a lot of people into a house, there are modifications done to the house," says John Avbar, a manager in bylaw enforcement for the City of Brampton. "Additional plumbing, wiring work, that sort of thing. Safety is paramount."

Avbar says the investigation and enforcement process, which can involve a bylaw officer entering a home, isn't difficult; it's just time-consuming. "My officers are also property standards officers. They respond to complaints from tenants and people living in rental accommodations when there are deficiencies that are not being maintained, that are not being rectified by a landlord."

Despite his feeling that many members of the public are ambivalent about secondary suites, Major Singh wants to make clear that there are some less obvious benefits to multi-generational housing. Having been a basement apartment dweller and someone who leaned on family for support at one point in his life, he says such living arrangements provide flexibility and helps prepare people for the realities of life.

"That's why it works better than apartment housing. People with families or children, they don't want to live in apartments. They want to live in a basement, make their savings, then get out to have their own house."

Submit a correction about this story